Cannabis (Marijuana) and Cannabinoids: What You Need To Know

Is marijuana the same thing as cannabis?

People often use the words “cannabis” and “marijuana” interchangeably, but they don’t mean exactly the same thing.

-

The word “cannabis” refers to all products derived from the plant Cannabis sativa.

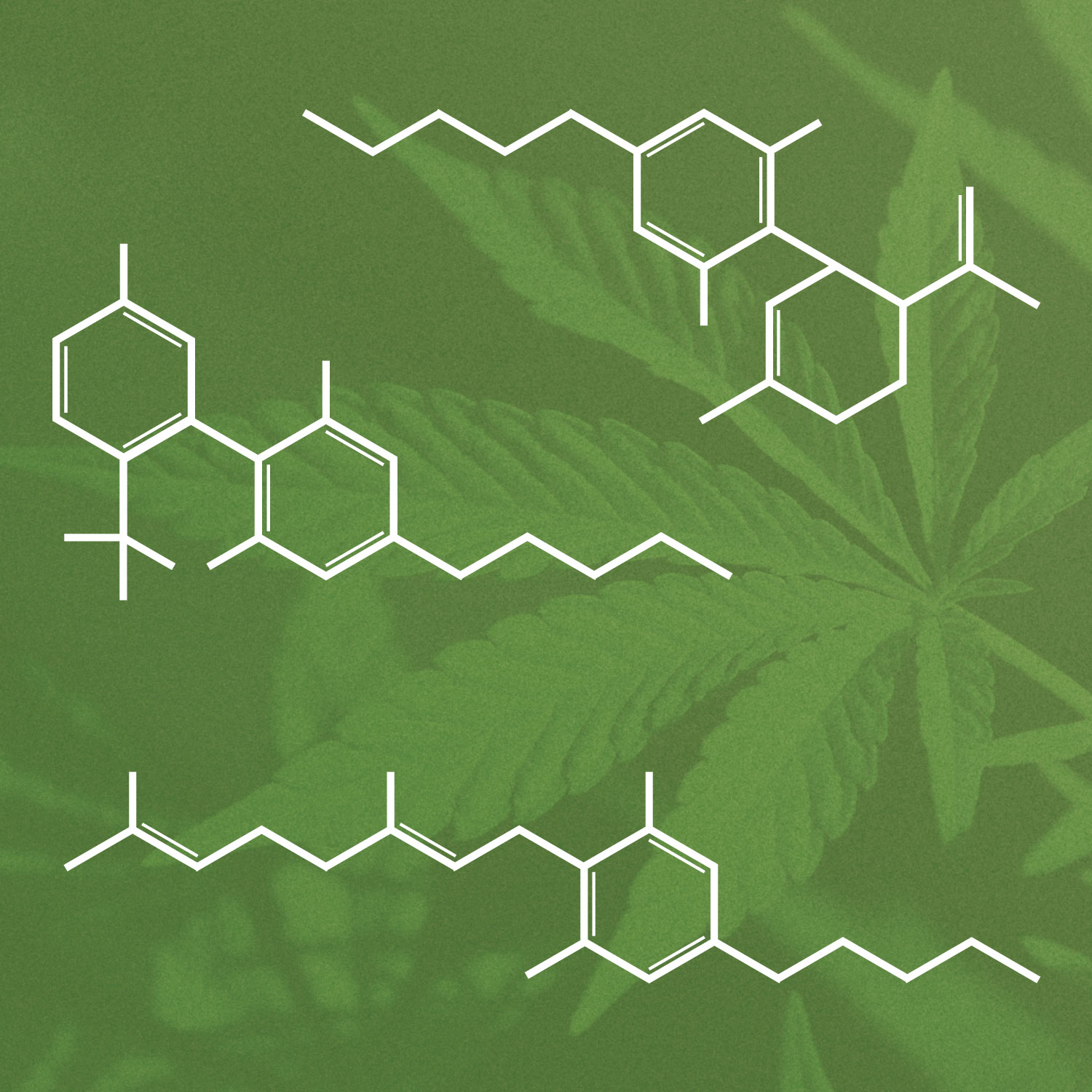

- The cannabis plant contains about 540 chemical substances.

- The word “marijuana” refers to parts of or products from the plant Cannabis sativa that contain substantial amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). THC is the substance that’s primarily responsible for the effects of marijuana on a person’s mental state. Some cannabis plants contain very little THC. Under U.S. law, these plants are considered “industrial hemp” rather than marijuana.

Throughout the rest of this fact sheet, we use the term “cannabis” to refer to the plant Cannabis sativa.

What are cannabinoids?

Cannabinoids are a group of substances found in the cannabis plant.

What are the main cannabinoids?

The main cannabinoids are THC and cannabidiol (CBD).

How many cannabinoids are there?

Besides THC and CBD, more than 100 other cannabinoids have been identified.

Has the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved cannabis or cannabinoids for medical use?

The FDA has not approved the cannabis plant for any medical use. However, the FDA has approved several drugs that contain individual cannabinoids.

- Epidiolex, which contains a purified form of CBD derived from cannabis, was approved for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome, two rare and severe forms of epilepsy.

- Marinol and Syndros, which contain dronabinol (synthetic THC), and Cesamet, which contains nabilone (a synthetic substance similar to THC), are approved by the FDA. Dronabinol and nabilone are used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by cancer chemotherapy. Dronabinol is also used to treat loss of appetite and weight loss in people with HIV/AIDS.

Is it legal for dietary supplements or foods to contain THC or CBD?

The FDA has determined that products containing THC or CBD cannot be sold legally as dietary supplements. Foods to which THC or CBD has been added cannot be sold legally in interstate commerce. Whether they can be sold legally within a state depends on that state’s laws and regulations.

Are cannabis or cannabinoids helpful in treating health conditions?

Drugs containing cannabinoids may be helpful in treating certain rare forms of epilepsy, nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy, and loss of appetite and weight loss associated with HIV/AIDS. In addition, some evidence suggests modest benefits of cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain and multiple sclerosis symptoms. Cannabis isn’t helpful for glaucoma. Research on cannabis or cannabinoids for other conditions is in its early stages.

The following sections summarize the research on cannabis or cannabinoids for specific health conditions.

Pain

- Research has been done on the effects of cannabis or cannabinoids on chronic pain, particularly neuropathic pain (pain associated with nerve injury or damage).

- A 2018 review looked at 47 studies (4,743 participants) of cannabis or cannabinoids for various types of chronic pain other than cancer pain and found evidence of a small benefit. Twenty-nine percent of people taking cannabis/cannabinoids had a 30 percent reduction in their pain whereas 26 percent of those taking a placebo (an inactive substance) did. The difference may be too small to be meaningful to patients. Adverse events (side effects) were more common among people taking cannabis/cannabinoids than those taking placebos.

- A 2018 review of 16 studies of cannabis-based medicines for neuropathic pain, most of which tested a cannabinoid preparation called nabiximols (brand name Sativex; a mouth spray containing both THC and CBD that is approved in some countries but not in the United States), found low- to moderate-quality evidence that these medicines produced better pain relief than placebos did. However, the data could not be considered reliable because the studies included small numbers of people and may have been biased. People taking cannabis-based medicines were more likely than those taking placebos to drop out of studies because of side effects.

- A 2015 review of 28 studies (2,454 participants) of cannabinoids in which chronic pain was assessed found the studies generally showed improvements in pain measures in people taking cannabinoids, but these did not reach statistical significance in most of the studies. However, the average number of patients who reported at least a 30 percent reduction in pain was greater with cannabinoids than with placebo.

Helping To Decrease Opioid Use

- There’s evidence from studies in animals that administering THC along with opioids may make it possible to control pain with a smaller dose of opioids.

- A 2017 review looked at studies in people in which cannabinoids were administered along with opioids to treat pain. These studies were designed to determine whether cannabinoids could make it possible to control pain with smaller amounts of opioids. There were 9 studies (750 total participants), of which 3 (642 participants) used a high-quality study design in which participants were randomly assigned to receive cannabinoids or a placebo. The results were inconsistent, and none of the high-quality studies indicated that cannabinoids could lead to decreased opioid use.

- Researchers have looked at statistical data on groups of people to see whether access to cannabis (for example, through “medical marijuana laws”—state laws that allow patients with certain medical conditions to get access to cannabis)—is linked with changes in opioid use or with changes in harm associated with opioids. The findings have been inconsistent.

- States with medical marijuana laws were found to have lower prescription rates both for opioids and for all drugs that cannabis could substitute for among people on Medicare. However, data from a national survey (not limited to people on Medicare) showed that users of medical marijuana were more likely than nonusers to report taking prescription drugs.

- An analysis of data from 1999 to 2010 indicated that states with medical marijuana laws had lower death rates from overdoses of opioid pain medicines, but when a similar analysis was extended through 2017, it showed higher death rates from this kind of overdose.

- An analysis of survey data from 2004 to 2014 found that passing of medical marijuana laws was not associated with less nonmedical prescription opioid use. Thus, people with access to medical marijuana did not appear to be substituting it for prescription opioids.

Anxiety

- A small amount of evidence from studies in people suggests that cannabis or cannabinoids might help to reduce anxiety. One study of 24 people with social anxiety disorder found that they had less anxiety in a simulated public speaking test after taking CBD than after taking a placebo. Four studies have suggested that cannabinoids may be helpful for anxiety in people with chronic pain; the study participants did not necessarily have anxiety disorders.

Epilepsy

- Cannabinoids, primarily CBD, have been studied for the treatment of seizures associated with forms of epilepsy that are difficult to control with other medicines. Epidiolex (oral CBD) has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of seizures associated with two epileptic encephalopathies: Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. (Epileptic encephalopathies are a group of seizure disorders that start in childhood and involve frequent seizures along with severe impairments in cognitive development.) Not enough research has been done on cannabinoids for other, more common forms of epilepsy to allow conclusions to be reached about whether they’re helpful for these conditions.

Glaucoma

- Glaucoma is a group of diseases that can damage the eye’s optic nerve, leading to vision loss and blindness. Early treatment can often prevent severe loss of vision. Lowering pressure in the eye can slow progression of the disease.

- Studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s showed that cannabis or substances derived from it could lower pressure in the eye, but not as effectively as treatments already in use. One limitation of cannabis-based products is that they only affect pressure in the eye for a short period of time.

- A recent animal study showed that CBD, applied directly to the eye, may cause an undesirable increase in pressure in the eye.

HIV/AIDS Symptoms

- Unintentional weight loss can be a problem for people with HIV/AIDS. In 1992, the FDA approved the cannabinoid dronabinol for the treatment of loss of appetite associated with weight loss in people with HIV/AIDS. This approval was based primarily on a study of 139 people that assessed effects of dronabinol on appetite and weight changes.

- There have been a few other studies of cannabis or cannabinoids for appetite and weight loss in people with HIV/AIDS, but they were short and only included small numbers of people, and their results may have been biased. Overall, the evidence that cannabis/cannabinoids are beneficial in people with HIV/AIDS is limited.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease is the name for a group of conditions in which the digestive tract becomes inflamed. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are the most common types. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, loss of appetite, weight loss, and fever. The symptoms can range from mild to severe, and they can come and go, sometimes disappearing for months or years and then returning.

- A 2018 review looked at 3 studies (93 total participants) that compared smoked cannabis or cannabis oil with placebos in people with active Crohn’s disease. There was no difference between the cannabis/cannabis oil and placebo groups in clinical remission of the disease. Some people using cannabis or cannabis oil had improvements in symptoms, but some had undesirable side effects. It was uncertain whether the potential benefits of cannabis or cannabis oil were greater than the potential harms.

- A 2018 review examined 2 studies (92 participants) that compared smoked cannabis or CBD capsules with placebos in people with active ulcerative colitis. In the CBD study, there was no difference between the two groups in clinical remission, but the people taking CBD had more side effects. In the smoked cannabis study, a measure of disease activity was lower after 8 weeks in the cannabis group; no information on side effects was reported.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is defined as repeated abdominal pain with changes in bowel movements (diarrhea, constipation, or both). It’s one of a group of functional disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that relate to how the brain and gut work together.

- Although there’s interest in using cannabis/cannabinoids for symptoms of IBS, there’s been little research on their use for this condition in people. Therefore, it’s unknown whether cannabis or cannabinoids can be helpful.

Movement Disorders Due to Tourette Syndrome

- A 2015 review of 2 small placebo-controlled studies with 36 participants suggested that synthetic THC capsules may be associated with a significant improvement in tic severity in patients with Tourette syndrome.

Multiple Sclerosis

- Several cannabis/cannabinoid preparations have been studied for multiple sclerosis symptoms, including dronabinol, nabilone, cannabis extract, nabiximols (brand name Sativex; a mouth spray containing THC and CBD that is approved in more than 25 countries outside the United States), and smoked cannabis.

- A review of 17 studies of a variety of cannabinoid preparations with 3,161 total participants indicated that cannabinoids caused a small improvement in spasticity (as assessed by the patient), pain, and bladder problems in people with multiple sclerosis, but cannabinoids didn’t significantly improve spasticity when measured by objective tests.

- A review of 6 placebo-controlled clinical trials with 1,134 total participants concluded that cannabinoids (nabiximols, dronabinol, and THC/CBD) were associated with a greater average improvement on the Ashworth scale for spasticity in multiple sclerosis patients compared with placebo, although this did not reach statistical significance.

- Evidence-based guidelines issued in 2014 by the American Academy of Neurology concluded that nabiximols is probably effective for improving subjective spasticity symptoms, probably ineffective for reducing objective spasticity measures or bladder incontinence, and possibly ineffective for reducing multiple sclerosis–related tremor. Based on two small studies, the guidelines concluded that the data are inadequate to evaluate the effects of smoked cannabis in people with multiple sclerosis.

- A 2010 analysis of 3 studies (666 participants) of nabiximols in people with multiple sclerosis and spasticity found that nabiximols reduced subjective spasticity, usually within 3 weeks, and that about one-third of people given nabiximols as an addition to other treatment would have at least a 30 percent improvement in spasticity. Nabiximols appeared to be reasonably safe.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Some people with PTSD have used cannabis or products made from it to try to relieve their symptoms and believe that it can help, but there’s been little research on whether it’s actually useful.

- In one very small study (10 people), the cannabinoid nabilone was more effective than a placebo at relieving PTSD-related nightmares.

- Observational studies (studies that collected data on people with PTSD who made their own choices about whether to use cannabis) haven’t provided clear evidence on whether cannabis is helpful or harmful for PTSD symptoms.

Sleep Problems

- Many studies of cannabis or cannabinoids in people with health problems (such as multiple sclerosis, PTSD, or chronic pain) have looked at effects on sleep. Often, there’s been evidence of better sleep quality, fewer sleep disturbances, or decreased time to fall asleep in people taking cannabis/cannabinoids. However, it’s uncertain whether the cannabis products affected sleep directly or whether people slept better because the symptoms of their illnesses had improved. The effects of cannabis/cannabinoids on sleep problems in people who don’t have other illnesses are uncertain.

Are cannabis and cannabinoids safe?

Several concerns have been raised about the safety of cannabis and cannabinoids:

- The use of cannabis has been linked to an increased risk of motor vehicle crashes.

- Smoking cannabis during pregnancy has been linked to lower birth weight.

- Some people who use cannabis develop cannabis use disorder, which has symptoms such as craving, withdrawal, lack of control, and negative effects on personal and professional responsibilities.

- Adolescents using cannabis are four to seven times more likely than adults to develop cannabis use disorder.

- Cannabis use is associated with an increased risk of injury among older adults.

- The use of cannabis, especially frequent use, has been linked to a higher risk of developing schizophrenia or other psychoses (severe mental illnesses) in people who are predisposed to these illnesses.

- Marijuana may cause orthostatic hypotension (head rush or dizziness on standing up), possibly raising danger from fainting and falls.

- The FDA has warned the public not to use vaping products that contain THC. Products of this type have been implicated in many of the reported cases of serious lung injuries linked to vaping.

- There have been many reports of unintentional consumption of cannabis or its products by children, leading to illnesses severe enough to require emergency room treatment or admission to a hospital. Among a group of people who became ill after accidental exposure to candies containing THC, the children generally had more severe symptoms than the adults and needed to stay in the hospital longer.

- Some long-term users of high doses of cannabis have developed a condition involving recurrent severe vomiting.

- There have been reports of contamination of cannabis/cannabinoid products with microorganisms, pesticides, or other substances.

- Some cannabis/cannabinoid products contain amounts of cannabinoids that differ substantially from what’s stated on their labels.

Can CBD be harmful?

Unlike Epidiolex (the purified CBD product sold as an FDA-approved prescription drug), over-the-counter CBD products may contain more or less CBD than stated on their labels, and because of less rigorous regulatory oversight than prescription drugs, they may also contain contaminants, such as THC.

CBD may have side effects, including decreases in alertness, changes in mood, decreased appetite, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea. CBD may also produce psychotic effects or cognitive impairment in people who also regularly use THC. In addition, CBD use has been associated with liver injury, male reproductive harm, and interactions with other drugs. Some side effects, such as diarrhea, sleepiness, abnormalities on tests of liver function, and drug interactions, appear to be due to CBD itself rather than contaminants in CBD products; these effects were observed in some of the people who participated in studies of Epidiolex before its approval as a drug.

Research Funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH)

Several NCCIH-funded studies are investigating the potential pain-relieving properties and mechanisms of action of substances in cannabis, including minor cannabinoids (those other than THC) and terpenes (substances in cannabis that give the plant its strain-specific properties such as aroma and taste). The goal of these studies is to strengthen the evidence regarding cannabis components and whether they have potential roles in pain management.

NCCIH is also supporting other studies on cannabis and cannabinoids, including:

- An observational study of the effects of edible cannabis and its constituents on pain, inflammation, and thinking in people with chronic low-back pain.

- Studies to develop techniques to synthesize cannabinoids in yeast (which would cost less than obtaining them from the cannabis plant).

- Research to evaluate the relationship between cannabis smoking and type 2 diabetes.

More To Consider

- Don’t use cannabis or cannabinoids to postpone seeing a health care provider about a medical problem.

- Take charge of your health—talk with your health care providers about any complementary health approaches you use. Together, you can make shared, well-informed decisions.

For More Information

NCCIH Clearinghouse

The NCCIH Clearinghouse provides information on NCCIH and complementary and integrative health approaches, including publications and searches of Federal databases of scientific and medical literature. The Clearinghouse does not provide medical advice, treatment recommendations, or referrals to practitioners.

Toll-free in the U.S.: 1-888-644-6226

Telecommunications relay service (TRS): 7-1-1

Website: https://www.nccih.nih.gov

Email: info@nccih.nih.gov (link sends email)

Know the Science

NCCIH and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provide tools to help you understand the basics and terminology of scientific research so you can make well-informed decisions about your health. Know the Science features a variety of materials, including interactive modules, quizzes, and videos, as well as links to informative content from Federal resources designed to help consumers make sense of health information.

Explaining How Research Works (NIH)

Know the Science: How To Make Sense of a Scientific Journal Article

PubMed®

A service of the National Library of Medicine, PubMed® contains publication information and (in most cases) brief summaries of articles from scientific and medical journals. For guidance from NCCIH on using PubMed, see How To Find Information About Complementary Health Practices on PubMed.

Website: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

MedlinePlus

To provide resources that help answer health questions, MedlinePlus (a service of the National Library of Medicine) brings together authoritative information from the National Institutes of Health as well as other Government agencies and health-related organizations.

Website: https://www.medlineplus.gov

Key References

- Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;(11):CD012853. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com/ on June 10, 2019.

- Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;(11):CD012954. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com/ on June 10, 2019.

- Lutge EE, Gray A, Siegfried N. The medical use of cannabis for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(4):CD005175. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com/ on June 10, 2019.

- Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;(3):CD012182. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com/ on June 10, 2019.

- National Academies. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research(link is external). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2017.

- Nielsen S, Sabioni P, Trigo JM, et al. Opioid-sparing effect of cannabinoids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(9):1752-1765.

- Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. Unintentional cannabis ingestion in children: a systematic review. Journal of Pediatrics. 2017;190:142-152.

- Segura LE, Mauro CM, Levy NS, et al. Association of US medical marijuana laws with nonmedical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid use disorder. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(7):e197216.

- Shover CL, Davis CS, Gordon SC, et al. Association between medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality has reversed over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116(26):12,624-12,626.

- Smith LA, Azariah F, Lavender VT, et al. Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;(11):CD009464. Accessed at https://www.cochranelibrary.com on June 10, 2019.

- Stockings E, Campbell G, Hall WD, et al. Cannabis and cannabinoids for the treatment of people with chronic noncancer pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and observational studies. Pain. 2018;159(10):1932-1954.

- Torres-Moreno MC, Papaseit E, Torrens M, et al. Assessment of efficacy and tolerability of medicinal cannabinoids in patients with multiple sclerosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(6):e183485.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Vaping illness update: FDA warns public to stop using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing vaping products and any vaping products obtained off the street. Accessed at https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/lung-injury-update-fda-warns-public-stop-using-tetrahydrocannabinol-thc-containing-vaping-products on October 9, 2019.

- Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456-2463.

- Yadav V, Bever C Jr, Bowen J, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline: complementary and alternative medicine in multiple sclerosis: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(12):1083-1092.

Other References

- Amin MR, Ali DW. Pharmacology of medical cannabis. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2019;1162:151-165.

- Bachhuber MA, Saloner B, Cunningham CO, et al. Medical cannabis laws and opioid analgesic overdose mortality in the United States, 1999-2010. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174(10):1668-1673.

- Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1995;10(2):89-97.

- Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RH, Chagas MH, et al. Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-naïve social phobia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(6):1219-1226.

- Bonn-Miller MO, Loflin MJE, Thomas BF, et al. Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1708-1709.

- Bradford AC, Bradford WD, Abraham A, et al. Association between US state medical cannabis laws and opioid prescribing in the Medicare Part D population. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018;178(5):667-672.

- Bradford AC, Bradford WD. Medical marijuana laws reduce prescription medication use in Medicare Part D. Health Affairs. 2016;35(7):1230-1236.

- Brodie MJ, Ben-Menachem E. Cannabinoids for epilepsy: what do we know and where do we go? Epilepsia. 2018;59(2):291-296.

- Caputi TL, Humphreys K. Medical marijuana users are more likely to use prescription drugs medically and nonmedically. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2018;12(4):295-299.

- Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN, et al. Association between nonmedical marijuana and pain reliever uses among individuals aged 50+. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(4):267-278.

- Gaston TE, Szaflarski JP. Cannabis for the treatment of epilepsy: an update. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2018;18(11):73.

- Goyal H, Awad HH, Ghali JK. Role of cannabis in cardiovascular disorders. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2017;9(7):2079-2092.

- Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235-1242.

- Jetly R, Heber A, Fraser G, et al. The efficacy of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares: a preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:585-588.

- Khattar N, Routsoloias JC. Emergency department treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a review. American Journal of Therapeutics. 2018;25(3):e357-e361.

- Kuhathasan N, Dufort A, MacKillop J, et al. The use of cannabinoids for sleep: a critical review on clinical trials. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2019;27(4):383-401.

- Lafaye G, Karila L, Blecha L, et al. Cannabis, cannabinoids, and health. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2017;19(3):309-316.

- Miller S, Daily L, Leishman E, et al. Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol differentially regulate intraocular pressure. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2018;59(15):5904-5911.

- National Cancer Institute. Cannabis and cannabinoids (PDQ®)—health professional version. Accessed at https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/cannabis-pdq#section/_1 on June 12, 2019.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIH research on marijuana and cannabinoids. Downloaded from https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/marijuana/nih-research-marijuana-cannabinoids on June 12, 2019.

- Novack GD. Cannabinoids for treatment of glaucoma. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2016;27(2):146-150.

- O’Connell BK, Gloss D, Devinsky O. Cannabinoids in treatment-resistant epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2017;70(Pt B):341-348.

- O’Neil ME, Nugent SM, Morasco BJ, et al. Benefits and harms of plant-based cannabis for posttraumatic stress disorder. A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017;167(5):332-340.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Cannabidiol (CBD): Potential Harms, Side Effects, and Unknowns. Accessed at https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep22-06-04-003.pdf on February 24, 2023.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA regulation of cannabis and cannabis-derived products: questions and answers. Accessed at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-questions-and-answers on June 12, 2019.

- Vandrey R, Raber JC, Raber ME, et al. Cannabinoid dose and label accuracy in edible medical cannabis products. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2491-2493.

- Vo KT, Horng H, Li K, et al. Cannabis intoxication case series: the dangers of edibles containing tetrahydrocannabinol. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2018;71(3):306-313.

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, et al. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(23):2219-2227.

- Wade DT, Collin C, Stott C, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of Sativex (nabiximols), on spasticity in people with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2010;16(6):707-714.

- Winters KC, Lee C-Y. Likelihood of developing an alcohol and cannabis use disorder during youth: association with recent use and age. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1-3):239-247.

Acknowledgments

NCCIH thanks D. Craig Hopp, Ph.D., Inna Belfer, M.D., Ph.D., and David Shurtleff, Ph.D., NCCIH, for their review of the 2019 edition of this publication.

This publication is not copyrighted and is in the public domain. Duplication is encouraged.

NCCIH has provided this material for your information. It is not intended to substitute for the medical expertise and advice of your health care provider(s). We encourage you to discuss any decisions about treatment or care with your health care provider. The mention of any product, service, or therapy is not an endorsement by NCCIH.