Appendix

Glossary of Terms

- Computerized Adaptive Testing: a form of computer-based testing that selects specific items for each individual based on their prior response to an item with the goal of maximizing precision.

- Computerized Adaptive Testing for Mental Health Disorders (CAT-MH™): a suite of measures validated for depression, anxiety, mania/hypomania, substance use disorder, psychosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, social determinants of health, adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and suicidality.

- Item Response Theory (IRT): one of several measurement theories that provides a framework for relating observed item and test scores to the latent variables that are directly relevant to assessment and diagnosis.

- Mechanistic and Clinical Outcomes: Mechanistic and clinical outcomes may be derived from studies using an intervention in healthy subjects or patients to better understand the clinical aspects of human biology and/or disease. More specifically, mechanistic outcomes provide insights into biological or behavioral processes, the pathophysiology of a disease, or the mechanism of action of an intervention (i.e., how it works). Clinical outcomes are measurable changes in health, function or quality of life that result from a treatment or intervention that is used to objectively determine the baseline function of a patient at the beginning of the interventional trial. Once the treatment or intervention has commenced, the same instrument can be used to determine progress and efficacy.

- Mechanistic Outcomes: Mechanistic outcomes provide insights into biological or behavioral processes, the pathophysiology of a disease, or the mechanism of action of an intervention (i.e., how it works).

- Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST): a novel framework developed to optimize interventions (i.e., to test the effectiveness of intervention delivery strategies using a factorial design).

- Music in Dementia Assessment Scales (MiDAS): scales developed to measure observable musical engagement of persons with moderate or advanced dementia who may have limited verbal skills to directly communicate their musical experiences.

- NIH EXAMINER: a neuropsychological test battery to reliably and validly assess domains of executive function (often defined as the ability to engage in goal-oriented behavior) for clinical investigations and clinical trials that is adaptable to a wide range of ages and disorders and captures real-life social and executive deficits.

- NIH Toolbox: a comprehensive set of neurobehavioral measurements that quickly assess cognitive, emotional, sensory, and motor functions from the convenience of an iPad.

- NIH Toolbox Emotion Module: a reasonably short measure of psychological well-being, general life satisfaction, meaning and purpose, self-efficacy, and social relationships. Each measure takes 1–2 minutes to complete and uses computer adaptive testing methods.

- Neuro-QoL (Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders): a measurement system that evaluates and monitors the physical, mental, and social effects experienced by adults and children living with neurological conditions.

- PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System): a set of person-centered measures that evaluates and monitors physical, mental, and social health in adults and children. It can be used with the general population and with individuals living with chronic conditions.

- SOBC (Science of Behavior Change) repository: a repository of behavioral science measures that have been validated (or are in the process of being validated) in accordance with the SOBC Experimental Medicine Approach. The SOBC Research Network has identified specific potential targets for behavior change interventions in the three broad domains of self-regulation, stress reactivity and stress resilience, and interpersonal and social processes.

Workshops

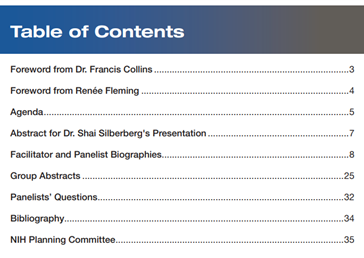

Workshop 1: Laying the Foundation: Defining the Building Blocks of Music-Based Interventions

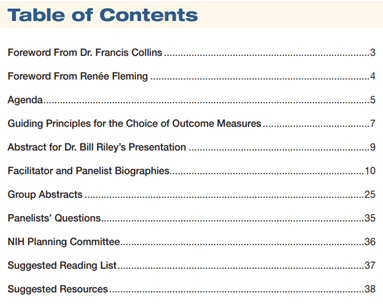

Workshop 2: Assessing and Measuring Target Engagement: Mechanistic and Clinical Outcome Measures for Brain Disorders of Aging

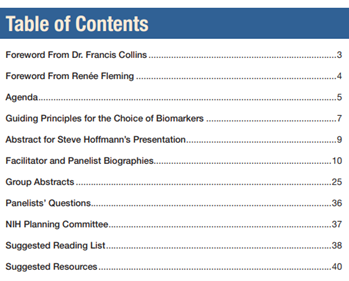

Workshop 3: Relating Target Engagement to Clinical Benefit: Biomarkers for Brain Disorders of Aging

Demonstration Projects

To culminate the workshop series and to illustrate the guiding principles for music based intervention (MBI) development and implementation, a subset of panel experts who participated across the workshop series were assembled into two interdisciplinary subgroups and asked to work together to develop and present a demonstration project. These subgroups were tasked to develop an MBI for a particular disease condition, applying the guiding principles identified over the course of the three-workshop series and specifying the research question, the theoretical framework, the building blocks of the proposed intervention, the outcome measures relevant to the clinical population, and the potential biomarkers to be studied. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) planning team saw this exercise as an opportunity to provide a more concrete example of how the MBI Toolkit could be utilized to develop research grant applications that include MBIs. Outlined below are the two prototype MBI studies, a listing of the multidisciplinary subgroups and outcomes of their discussions.

Project 1: The Effects of Therapeutic Choir on Wellbeing of Care Recipient-Caregiver Dyad—A Demonstration Project

Expert Panelists (detailed credentials are listed in the Program Book for each workshop in the Appendix)

| Panelist Subgroup | Name |

|---|---|

| Behavioral & Social Science Intervention Development | Sona Dimidjian Susan Landau |

| Clinical Trials Methodology | Roger Fillingim Ken Freedland |

| Music Therapy/Music Medicine | Melita Belgrave Joke Bradt Edward Roth |

| Neuroscience | Daniel Levitin Psyche Loui |

| Patient and Arts Advocacy | Barbara Else Anne Leonard Susan Magsamen Bruce Miller |

Background and Rationale

- Agitation (i.e., excessive psychomotor activity, physical or verbal aggression, disruptive irritability, and/or disinhibition) is a common symptom among patients with dementia, affecting 40%–60% older adults with mild to moderate AD (Halpern et al., 2018)

- Anxiety symptoms occur in 70% of older adults with mild to moderate AD and are significantly correlated with impairments in Activities of Daily Living

Gap/Need

- Music-Based Intervention for Well-being

- Good amount of MBI research on effects of MBI on reduction of agitation and anxiety in Care Recipients (CR) BUT little on reduction of stress and caregiver burden, and enhanced coping in Caregiver (CG).

- Also, little data on MBI in biomarker-validated AD

- Dyad as a core feature of this demonstration study

- prevalence of community-based caregiving in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early AD

- CG burden especially in psychosocial domain (stress and coping, quality of life) relative to participant symptoms (anxiety, agitation)

Study Aims

- Aim 1. To examine the effects of participation in therapeutic choir on agitation and anxiety in care recipients with AD

- Aim 2. To examine the effects of participation in therapeutic choir on stress, loneliness, caregiver burden, and quality of life

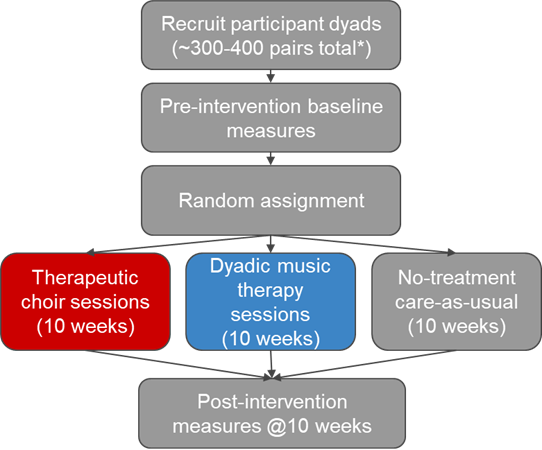

Study Design

Participants

- Community-dwelling home-based dyads

Eligibility criteria

Care Recipient:

- Clinical diagnosis of AD

- Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) of 1 to 2: mild to moderate AD

- Amyloid positive at baseline (plasma measurement)

- Moderate to severe agitation (Agitation scale on Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) ≥ 2), caregiver stress (PSS ≥ 12)

Caregiver:

- At least mild levels of caregiver distress: average NPI score of caregiver distress ≥ 2 (mild and above)

- Perceived Stress Scale

- UCLA Loneliness Scale

Sample Size Considerations

Sample size determined from previous studies

- Anticipated effect size / Minimally clinically significant difference

- Power

- Alpha-level

- Anticipated attrition

- Type of statistical test to be used

Proposed Intervention—Therapeutic Choir

10-week therapeutic choir intervention with a performance at the end

Repertoire consists of familiar and unfamiliar music

Weekly Intervention

- 5 minutes vocal warm-up

- 5 minutes receptive music experience

- 30 minutes active music making (group experiences)

- Singing, singing + instrument playing, song writing, developing and learning arrangements (unison and harmony singing, solo and group experiences)

- 5 minutes wrap-up

- 10–15 minutes post therapeutic choir socialization

Performance

- Public or private performance of songs learned during 10-week intervention (8-10 songs familiar and unfamiliar music)

Proposed Intervention—Individual Dyads

10-week individual music therapy sessions with dyads

Repertoire consists of familiar and unfamiliar music

Weekly Intervention

- 5 minutes vocal warm-up

- 5 minutes receptive music experience

- 45 minutes active music making (dyad experiences)

- Singing, singing + instrument playing, song writing, lyric discussion

- 5 minutes wrap-up

Outcomes – Aim 1

Primary outcome measure: CR agitation

Instruments:

- NPI-Q

- Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory—Short Form (CMAI-SF)

Secondary outcome measure: CR anxiety

Instruments:

- Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) or RAID

- Cortisol biomarker

- Home collection: morning for 3 consecutive days

- Before and after sessions

Outcomes—Aim 2

Primary Outcome: Caregiver stress

Instruments:

- Perceived Stress Scale

- Cortisol biomarker

- Home collection: morning for 3 consecutive days

- Before and after sessions

Secondary Outcomes

- CG loneliness

Instruments:

- Caregiver Loneliness: UCLA Loneliness Scale

- CG burden

- Resilience Scale

- NPI caregiver distress

- Zarit Burden Interview (SF)

- CG quality of life

- Assessment of Quality of Life-6D

- AMA Caregiver Self-Assessment Questionnaire

Confounding Variables

Important to measure and track potential confounders, e.g.:

- Clinical severity

- Past music experience/training

- Socioeconomic status

- Participation in other socially engaging activities

- Other music-making experiences that take place during and outside of the trial

Project 2: Can the Motor and/or Non-Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease (PD) Be Improved With a Music-Based Intervention (MBI)? A Theoretical Study Design

Expert Panelists (detailed credentials for the panelist are listed in the Program books for the workshops in the Appendix)

| Panelist Subgroup | Name |

|---|---|

| Behavioral & Social Science Intervention Development | Bryan Denny |

| Eric Garland | |

| Assal Habibi | |

| Clinical Trials Methodology | Sheri Robb |

| Carlie Tanner | |

| Music Therapy/Music Medicine | Julene Johnson |

| Michael Thaut | |

| Neuroscience | John Iversen |

| Nina Kraus | |

| Josh McDermott | |

| Patient and Arts Advocacy | Rebecca Gilbert |

| Sunil Iyengar |

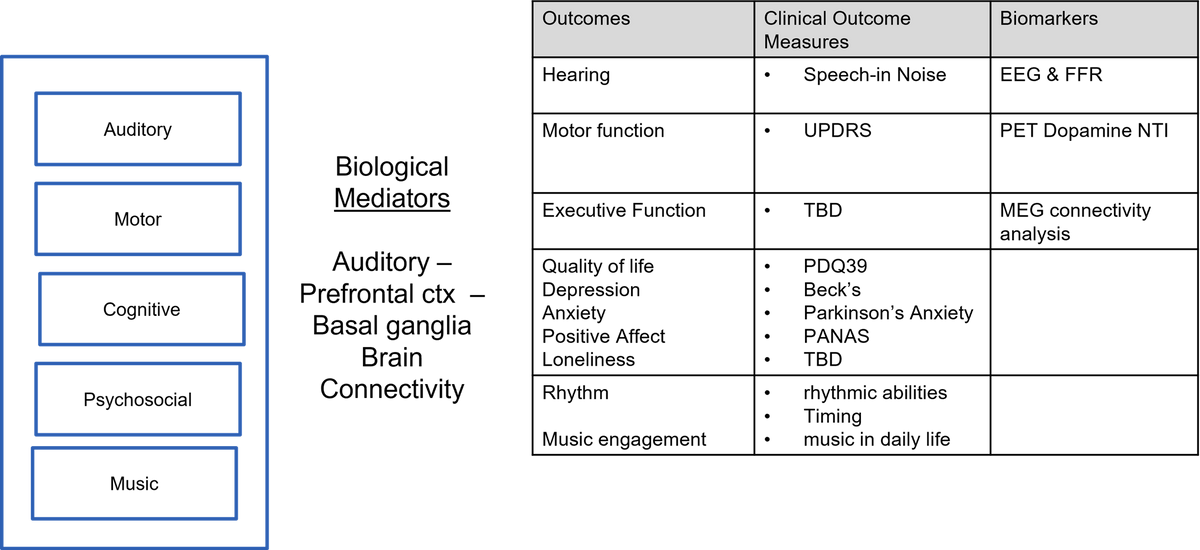

Study Design

A multi-centered study comparing different potential MBIs (as an example: dance vs music\treadmill vs treadmill) to see if there are greater benefits from one or the other. One might hypothesize that dance might provide a more holistic benefit, given the social aspects as well as the benefits of music and movement, followed by music\treadmill, and least benefit from treadmill.

Population

Enroll all stages of PD and even people with prodromal disease, such as those with REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. Enroll from each group, sufficient to allow subgroup analyses as well as a global analysis.

Control Population

- If studying a group-based MBI, then choose as control people with PD receiving another group-based activity (to control for the benefits conferred by a group-based activity)

- People without PD undergoing a group-based MBI (to compare biomarker outcomes and mechanistic measures)

Consideration of Outcomes

Outcome Measures

Effectiveness of musical intervention in musical terms

Assessment of:

- Rhythmic abilities

- Timing

- Musical/social engagement

- Increased use of music in daily life

- Musical history

Non-Motor Symptom Assessment

- PDQ39 - quality of life

- MoCA - Montreal cognitive assessment, other tests of cognition

- Beck’s Depression Inventory

- Measurements of social isolation/social connection, negative thought patterns

- Parkinson Anxiety Scale

- Caregiver burden Scale - measuring partner stress and quality of life, and for more advanced disease, care partner stress and quality of life

- Hearing Speech in Noise

- MDS non-motor symptom scale

Motor Symptom Assessment

- Quantitative motor tests for gait and balance

- Remote assessment using digital biomarkers (outside of clinic, e.g., phone based).

- Standard UPDRS

All motor assessments would need to be performed ON and OFF medication.

Compliance: A more practical question might be to explore the determinants of persistence with treatment. If there are home based aspects of the treatment, would want to be able to assess compliance.

Biomarkers

- FFR—an EEG biomarker that measures sound processing in the brain with granularity

- Other EEG assessment of sensorimotor system function, whether it be resting state or beta-band connectivity or rhythm/music-evoked activity

- Measurement of auditory function—given the interest in understanding the relationship between changes in auditory function and response to therapy, this could be important

- MEG to assess connectivity

- A blood test marker of stress (cortisol) or inflammation

- PET to assess neurotransmitters

- fMRI using tasks with a focus on the reward system and decision making

- Measures to be done pre-intervention, at 12 weeks, and 3 months after intervention

Additional feedback and input on the MBI Toolkit were also gathered from the public through a formal request for information (RFI).

NOT-AT-21-011

Request for Information (RFI): Inviting Comments on Developing Evidence-Based Music Therapies for Brain Disorders of Aging. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-AT-21-011.html (released May 20, 2021 and closed on June 30, 2021).

Additional Study Design Considerations

Study designs are the set of methods and procedures used to collect and analyze data in a study. In designing randomized controlled music-based intervention studies, music and health researchers should clearly define and justify the number and length of sessions as well as the duration of the intervention. Moreover, researchers must clearly indicate and justify the sample size of the proposed study, the power calculation, the chosen control condition or comparator, the blinding and randomization schemes. For some MBIs there might not be sufficient evidence to design a structured randomized controlled trial as a first step. Under such circumstances, investigators should then consider frameworks for intervention development and optimization, including the framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions1 and the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and collaborative planning approach,2 which include a preparation stage (formative work), pilot testing (which may not involve randomization), and then a small factorial or other randomized controlled trial design that informs how to put together the optimized intervention. These stages precede formal efficacy and effectiveness testing.2 Conducting well-designed interviews (qualitative analysis) with participants is an essential feature of studies that seek to understand the mechanisms and outcomes of an intervention before embarking on a larger, controlled trial.

Minimizing the risk of bias is critical when planning, conducting, analyzing, and interpreting interventional studies. A systematic review of 50 studies investigating the effects of music-based interventions on pain and anxiety in children and adults undergoing medical procedures, revealed that 84% had a high risk of bias. The study concluded that to improve research quality and reduce risk of bias investigators needed to carefully consider several factors, including randomization, treatment allocation concealment, blinding outcome assessors, and intention-to-treat analysis.3 Every attempt should be made to ensure equal conditions and handling for the comparison groups except for the parameters being tested.

Blinding minimizes the potential risk of bias and, ideally, should be applied at all stages of the study, including subject allocation, data collection, and data analysis. However, with MBIs, blinding participants, in most cases, will not be possible. Expectations of treatment effects could influence the neuropsychological and clinical outcomes in clinical trials of behavioral and lifestyle interventions and could potentially confound the interpretation of findings. Thus, measuring and accounting for expectancy and credibility are important.4

Other critical study design considerations include participant burden and caregiver participation. Involving participants’ perspectives/input early in the research process is important in informing the overall study design. Moreover, acceptability and generalizability of the intervention can better facilitate dissemination and implementation of the intervention across sites and health care systems.

Determination of the relevant outcome measures in a music-based intervention for brain disorders of aging will ultimately depend on the research question, the specific intervention, the study population, and the aims of the study. The experiences of patients and caregivers need to be primary determinants of the research questions to be addressed, and consideration should be given to the impact on subject burden and the number of outcome measures. When selecting primary outcomes for MBI studies, two competing considerations need to be balanced: maximizing the impact of the intervention and maximizing the importance of the outcome for public health. The impact of the intervention can be maximized by choosing outcomes that are closely aligned with and proximal to the target of the intervention. For example, a music listening intervention study aimed at improving behavioral symptoms in people living with dementia may measure reduced agitation as a proximal outcome (change during and after listening) while improved quality of life may be assessed as a more distal outcome (potential benefit over a period of time). Intermediate or surrogate outcomes that have been associated with distal (long-term) outcomes can also be useful.5

The choice of secondary outcomes should be justified. It is advisable to choose secondary outcomes that are proximal or distal to the intervention, theoretical mediators of change, or measures that will help explain a null effect. Adjustment for multiple comparisons is also important.

In selecting biomarkers for MBI trials, investigators should recognize that music could affect a clinical outcome through a mechanism that is independent of the pathophysiology of the disease, and that both disease-specific and outcome-specific mechanisms should be considered in biomarker selection. For example, inflammation is not considered a primary disease mechanism but can influence disease progression and may be responsive to interventions. Though diagnostic markers (beta-amyloid and tau for AD and alpha-synuclein for PD) may be useful for observational or mechanistic studies, their utility in the context of MBI trials is limited. MBIs are most likely to influence symptoms of disorders of aging (e.g., irritability, depression, task handling, stress, disorientation) rather than the course of a disease.

References

- Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. Bmj 2000; 321: 694–6.

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART): New Methods for More Potent eHealth Interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2008; 11.

- Yinger OS, Gooding LF. A systematic review of music-based interventions for procedural support. J Music Ther 2015; 52: 1–77.

- Haddad R, Lenze EJ, Nicol G, Miller JP, Yingling M, Wetherell JL. Does patient expectancy account for the cognitive and clinical benefits of mindfulness training in older adults? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020; 35: 626–32.

- Freedman LS, Graubard BI, Schatzkin A. Statistical validation of intermediate endpoints for chronic diseases. Stat Med 1992; 11: 167–78.